'That's vanity ... not politics," President John F. Kennedy once snapped at an aide who wanted him to provoke a confrontation with Congress on an issue Kennedy knew he didn't have the votes to pass.

'That's vanity ... not politics," President John F. Kennedy once snapped at an aide who wanted him to provoke a confrontation with Congress on an issue Kennedy knew he didn't have the votes to pass.Times change, don't they?

Now many in Washington believe the essence of politics is provoking confrontations over issues that have little chance of becoming law but a high probability of dividing the country.

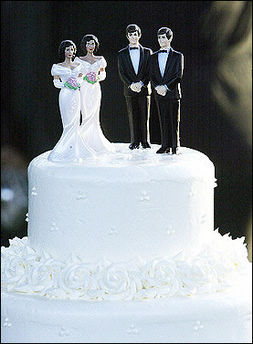

Exhibit A is this week's planned Senate vote on a proposed constitutional amendment to prohibit gay marriage. No one doubts the outcome. Proposed constitutional amendments require a two-thirds majority — 67 votes — to clear the Senate. When the Senate last considered the gay marriage ban, in July 2004, supporters mustered only 48 votes on a procedural test. The backers might do better this time, but they are unlikely to get close to the votes they need.

One big reason is that supporters haven't built a clear majority for the momentous step of amending the Constitution. In surveys, most Americans say they oppose legal recognition for gay marriages. But many appear comfortable allowing the states, which have traditionally regulated marriage, to handle the issue.

In the latest Gallup Poll, 50% said they supported a constitutional ban on gay marriage; 47% opposed it. Nine other Gallup surveys since 2003 have produced similar results. There's no evidence supporters have established the overwhelming social consensus that should accompany any effort to amend the Constitution on this issue.

But like so much else in contemporary politics, the Senate vote isn't designed to produce a law; it's intended to pick a fight. The White House and Senate GOP leadership are betting that a noisy confrontation over gay marriage will encourage turnout this November from conservative voters — many of whom, polls show, are discouraged over President Bush's second term.

That strategy may help Republicans in some red states this year. But it could also deepen the image of intolerance hurting the GOP in many white-collar suburbs outside the South. Either way, these near-term, tactical calculations don't represent the most important political consequence: Both parties may pay a long-term price if manufactured cultural clashes such as the gay marriage amendment continue to control the spotlight.

Whatever else Americans may think about gay marriage, few consider it one of the country's most serious moral challenges. By elevating it so prominently, this week's debate is likely to deepen the sense that Washington is fixated on the preoccupations of ideological minorities while slighting most Americans' day-to-day concerns.

That danger is captured in a national survey due to be released Monday by the liberal Center for American Progress. The survey, conducted in late February, underscores the importance of religion and morality in Americans' lives. Nearly three-quarters of those polled said they prayed at least once a day, and just over half said they attended religious services at least once a week. Concern that the country had lost its moral compass was widespread.

But the survey demonstrated again that the moral issues people worried about most in their daily lives were very different from the ones dominating political debate. The survey asked Americans to name the most serious moral crisis in America today. Atop the list, 28% cited "kids not raised with the right values." Next came corruption in government and business, followed by greed and materialism, people too focused on themselves, and too much sex and violence in the media. Only 3% named abortion and homosexuality as the nation's top moral challenge. Even among those who attend religious services most often, just 6% picked abortion and homosexuality.

These findings challenge the values agenda of both parties. They do point to priorities different from the conservative focus on gay rights and abortion. But they also suggest liberals don't hit the mark either when they try to signal their values simply by describing causes, such as reducing poverty, as moral imperatives.

"There is a deep hunger to get away from religion being associated solely with the antiabortion and anti-gay marriage agenda — there is a deep public yearning for an alternative moral vision," said John Halpin, a senior fellow and opinion analyst at the Center for American Progress. "But it's not just talking about the left's issues and tagging the word 'moral' on it. You have to talk to people at a personal and family level about what faith and values mean."

Public policy can't easily reach all of these anxieties. But it can address some of them. Government can do more to support parents who believe they are competing with a rapacious marketplace to shape their children's values.

One example: The day after the Senate rejected the gay marriage amendment in 2004, it gave broad bipartisan approval to legislation that would have empowered the Food and Drug Administration to regulate tobacco — including the marketing of cigarettes to young people. That idea died when the House said no. Senators from both parties are pushing the tobacco issue again. Surely a Senate leadership that has time for a symbolic statement about gay marriage could find a moment to help parents fight the tangible problem of teen smoking.

Washington might support parents in many other ways. (President Clinton pioneered this path, although often with modest steps, with the "tools for parents" initiatives he launched in his first term.) But, as Halpin suggests, Americans probably aren't looking to Washington for programs so much as evidence it understands the cultural forces pressing upon communities and families.

It's difficult to see how the Senate sends that signal by squandering its time on a choreographed argument over gay marriage staged for no higher purpose than dividing the country.

from The Los Angeles Times

No comments:

Post a Comment