When Egyptologists entered the tomb for the first time more than four decades ago, they expected to be surprised. Explorers of newly exposed tombs always expect that, and this time they were not disappointed - they were confounded.

When Egyptologists entered the tomb for the first time more than four decades ago, they expected to be surprised. Explorers of newly exposed tombs always expect that, and this time they were not disappointed - they were confounded.It was back in 1964, outside Cairo, near the famous Step Pyramid in the necropolis of Saqqara and a short drive from the Sphinx and the pyramids at Giza. The newfound tomb yielded no royal mummies or dazzling jewels. But the explorers stopped in their tracks when the light of their kerosene lamp shined on the wall art in the most sacred chamber.

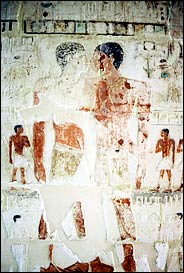

There, carved in stone, were the images of two men embracing. Their names were inscribed above: Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. Though not of the nobility, they were highly esteemed in the palace as the chief manicurists of the king, sometime from 2380 to 2320 B.C., in the time known as the fifth dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Grooming the king was an honored occupation.

Archaeologists were taken aback. It was extremely rare in ancient Egypt for an elite tomb to be shared by two men of apparently equal standing. The usual practice was for such mortuary temples to be the resting place of one prominent man, his wife and children.

And it was most unusual for a couple of the same sex to be depicted locked in an embrace. In other scenes, they are also shown holding hands and nose-kissing, the favored form of kissing in ancient Egypt.

What were scholars to make of their intimate relationship?

Over the years, the tomb's wall art has inspired considerable speculation. One interpretation is that the two men were brothers, probably identical twins, and this may be the earliest known depiction of twins. Another is that the men had a homosexual relationship, a more recent view that has gained support among gay advocates.

Now, an Egyptologist at New York University has stepped into the debate with a third interpretation. He has marshaled circumstantial evidence that the two men might have been conjoined twins, popularly known as Siamese twins. The expert, David O'Connor, a professor of ancient Egyptian art at the university's Institute of Fine Arts, said: "My suggestion is that Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were indeed twins, but of a very special sort. They were conjoined twins, and it was this physical peculiarity that prompted the many depictions of them hand-holding or embracing in their tomb-chapel."

O'Connor elaborated on his hypothesis in a recent lecture and in an interview in New York. He will further describe and defend the idea at a conference, "Sex and Gender in Ancient Egypt," this week at the University of Wales in Swansea.

Opposition to his proposal promises to be spirited. Most Egyptologists accept the normal-twins interpretation advanced most prominently by John Baines, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford in England.

"It's a very persuasive case Baines makes," O'Connor acknowledged.

And he noted that the gay-couple hypothesis had become the popular idea in the last decade. A leading proponent is Greg Reeder, an independent scholar in San Francisco and a contributing editor of KMT, a magazine of Egyptian art and history. The most Google references to the tomb, archaeologists say, concern the homosexual idea.

The gay argument leans on the analogy with depictions of married heterosexual couples in Egyptian art, which was first suggested by Nadine Cherpion, a French archaeologist.

Because the embraces of heterosexual couples in the tomb art convey an implicit erotic and sexual relationship, and perhaps the belief of its continuation in the afterlife, Reeder and his allies contend that similar scenes involving the two men have the same significance, that they presumably are gay partners.

Calling attention to the most intimate scene of the two embracing men, Reeder said: "They are so close together here that not only are they face to face and nose to nose, but so close that the knots on their belts are touching, linking their lower torsos. If this scene were composed of a male-female couple instead of the same-sex couple we have here, there would be little question concerning what it is we are seeing."

In an interview last week, Reeder said that O'Connor's new interpretation was fascinating, but added, "It's the most extreme and unnecessary theory." Baines, in an e-mail message from Oxford, said that he "would stick with my own interpretation, because it seems to me to require the smallest amount of 'exceptionalism' and to fit reasonably well with other patterns."

As for the sexual implications of the embracing poses, Baines has suggested that they could signify the "socially and emotionally linked roles" of two men who probably were twins.

Or they could symbolize "protection or close identification and reciprocity" between the two.

Ancient Egyptian art, experts say, is not meant always to be taken literally.

James Allen, an Egyptologist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art who is not involved in the research, called the twins hypothesis probable and the conjoined-twins idea "an interesting wrinkle." The least likely, he said, was the homosexual relationship proposal.

Baines said, "The gay-couple idea is essentially derived from imposing modern preoccupations on ancient materials and not attending to the cultural context."

If O'Connor is correct, the tomb holds a rare example that far back in history of documented conjoined twins, he said, and thus an insight into ancient Egyptian attitudes toward disabilities. He cited other records, and art of the dwarf Seneb, who in a somewhat later court was "overseer of dwarfs in charge of dressing" the king and a tutor of the royal sons, both positions of elite status. Egyptians appear to have viewed such people as auspicious figures, not freaks.

The apparently close relationship and equal standing of the two men are illustrated not only in images of them together, either holding hands or embracing. In other instances, O'Connor said, one man appears alone on a wall face, and the other on the opposing wall. Their stature and pose are identical, and they are performing similar acts.

While one fishes in the marshes, for example, the other hunts birds in the same setting.

These scenes and the ones of intimate embraces led to the speculation, initially by Mounir Basta, the Egyptian archaeologist who first explored the tomb, that Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were brothers, probably twins. Baines developed the idea in a seminal study in the 1980s, and others took up the gay-couple idea.

When O'Connor looked into the matter, he was struck by a comparison of the images of the two men with pictures of Chang and Eng, the famous conjoined twins born in 1811 in Siam. They were seen close together, arm in arm. They and a number of documented conjoined twins also had wives and children - like the two Egyptians - and engaged in strenuous activities, much like the hunting and fishing of the two Egyptians.

Their names, Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, suggest another clue, O'Connor said. Both names refer to the god Khnum, the deity who fashions the form of a child in the womb. Though not an uncommon part of Egyptian names, in this case it might be a play on words to signify their paired lives.

David Silverman, an Egyptologist at the University of Pennsylvania, and his student Joshua Robinson pointed out to O'Connor that the name Khnum was also similar to the ancient Egyptian word khenem, which means "to unite" or "be united."

One problem, however, is that none of the tomb art shows a physical link between the two men, as in some pictures of Chang and Eng.

Whether the two men were normal twins, conjoined twins or a gay couple, the speculation highlights a problem and an opportunity for scholars.

"We don't have a lot of information about how twins were viewed in ancient Egypt or how gay life was perceived," said Allen, of the Metropolitan Museum.

Few accounts refer to twins of any kind in the civilization, and an honored role for conjoined twins, if that is what they were, would be even stronger evidence of Egyptian attitudes toward people with physical disabilities.

"Such attributes were often seen as fabulous rather than monstrous, and positive rather than negative," O'Connor said.

"They attested the creator god's ability, if he wished, to bring wondrous changes upon the norms he himself had established."

Besides, O'Connor pointed out, "the fact that they could have worked simultaneously on the grooming of the king's two hands might have been seen as especially appropriate and desirable."

Homosexuality was only occasionally referred to in Egyptian documents, sometimes in myths of certain gods, implying that it was not considered a normal relationship. The prevailing attitude, scholars say, was not antigay, though probably negative, and certainly not as accepting of homosexual activity as in classical Greece.

If the tomb of the two men was indeed a public profession of their emotional and sexual attachment, scholars say, it could inspire a reassessment of the place of homosexuals in Egyptian culture.

Defending his interpretation, Reeder said the similarity of the embracing scenes with those of husbands and wives should not be dismissed. He further noted, in his lecture in Wales, new evidence that he said suggested that one of the men died well before the other.

Khnumhotep was described in one place as being honored by a great god, possibly meaning he had by then entered the afterlife, while in a corresponding scene Niankhkhnum had only official titles of his career in life.

If, then, Niankhkhnum was the one who finished decorating the tomb, Reeder said, it was unlikely that they were conjoined twins.

"They would have had to be surgically separated," he said in an interview. "The Egyptians had surgical knowledge. But separating such twins would be expecting too much."

The fact that the two men had families is not seen as contradicting the gay hypothesis, Egyptologists said. Like others of the time, the two men would presumably have sired children to carry on after them and maintain the cult dedicated to their well-being through eternity.

Reeder said his hypothesis "resonates in the gay community because it shows two historical men being intimate with each other, and this was something that could be shown in an ancient culture."

O'Connor acknowledged the interpretation's appeal. "Gays and lesbians still experience a great deal of prejudice and discrimination, and these two ancient Egyptians are yet further proof that homosexuality goes far back in history," he said.

"The semipublic nature of their tomb chapel," he added, "suggests their gay relationship was accepted as normative by the elite of a particularly famous and illustrious civilization."

Finally, O'Connor conceded that the conjoined-twins hypothesis, like the other two, is not "fully supported by conclusive evidence."

from International Herald Tribune

No comments:

Post a Comment