As a lesbian who came out in the 1970s, I was never an advocate of gay marriage. It seemed too straight, too assimilative, too much like heterosexuality. But I applaud the recent ruling in my native state of New Jersey that gay couples are entitled to full legal rights and financial benefits.

As a lesbian who came out in the 1970s, I was never an advocate of gay marriage. It seemed too straight, too assimilative, too much like heterosexuality. But I applaud the recent ruling in my native state of New Jersey that gay couples are entitled to full legal rights and financial benefits.I have learned the hard way why these rights are necessary.

I just got divorced - at least as far as I am concerned. But in the eyes of New York State, my relationship with a woman was never a legal bond. After devoting 26 years to our relationship, all I've got is a worthless domestic partnership agreement, two boxes full of photos of us together and bundles of cards saying how much she loves me.

We were giddy that day in 1993 when we finally could register our union at the Municipal Building in lower Manhattan, shortly after the city had passed its domestic partnership legislation. This document offered only a few local benefits, but it was as significant to us as a marriage license.

Like anyone getting married, I never thought we'd go the route of the 50 percent of couples who end up divorced. But now that we have, I find that I can't hire a divorce lawyer because I have no legal rights.

As a freelance writer, I never made enough money to save. My partner, "Slim," a photographer, made a lot more than I. Her savings were to be our retirement plan.

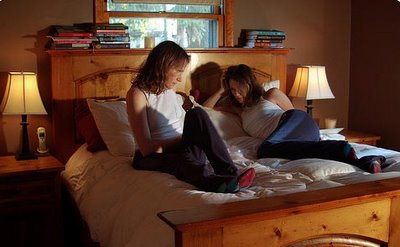

I launched her photography career by accident when I asked her to take some pictures to accompany my stories. On our 25th anniversary card, she wrote that her career was forever dedicated to me. But over the next year, Slim had a midlife crisis. She had married her high school sweetheart at 20, and we hooked up not long after that ended. I had led a much more experimental sex life before we met. Now, struck by her mortality, she was curious to do in middle age what I'd done in my younger days - explore what's out there.

After the breakup, my friends rallied, treating me to dinner and inviting me to their beach houses. To them, I was the loyal 57-year-old wife whose spouse had gotten bored and walked out. I tried to find a way to save the relationship; I talked to my shrink, wrote in my journal, cried a lot. I lost sleep and dropped 12 pounds on the breakup diet.

But Slim felt that the only way she could leave me was by going "cold turkey." It feels more like a death than a separation, and without any closure.

If we were married, the ending would have been neater and much less abrupt. We would still have some contact, getting together our affairs during the transition. I could hand my lawyer a list of items I wanted, and he could negotiate for them. Most important, my lawyer could argue for equitable distribution of Slim's IRAs and savings accounts.

My name is listed as beneficiary but, not being married, I have no legal claim to the money until Slim is dead. This six-figure nest egg was earmarked for our retirement, or so she said as she socked it away.

We'd always been opposites. She was a workaholic who did not cultivate friendships. I have many chums and interests. She avoided introspection and did not believe in therapy. I was emotionally open. She was a control freak. I was a nurturer who bent over backward to please her. She felt unable to have a full life and stay in the relationship.

How funny that a Greenwich Village lesbian couple could turn out to be such a middle-American cliche of a heterosexual marriage. I'd played the stereotypical sensitive female role. She was the stoic male.

For more than a quarter century, I was a fool in love with no legal protection other than a will. Now I'm alone and panicked about my future. I was not only dumped emotionally, but left in a fragile economic situation.

How ironic that this personal tragedy has turned me into a champion of a legal convention that I once found far too traditional. Despite our downtown lifestyle, the old-fashioned institution of marriage turns out to provide protection I never expected to need.

from Newsday / Kate Walter

No comments:

Post a Comment