Some movies only look modest. They ply an understated aesthetic and an unassuming rhythm. They often employ a cast featuring nonprofessional or little-known talent. Occasionally, they take the big prize at that indie bazaar, the Sundance Film Festival.

Some movies only look modest. They ply an understated aesthetic and an unassuming rhythm. They often employ a cast featuring nonprofessional or little-known talent. Occasionally, they take the big prize at that indie bazaar, the Sundance Film Festival.Not until this year, though, has one of their ilk taken home both the Dramatic Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award for an American feature.

Co-writers/co-directors Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland and their cast of relative unknowns pulled off this indie coup in January.

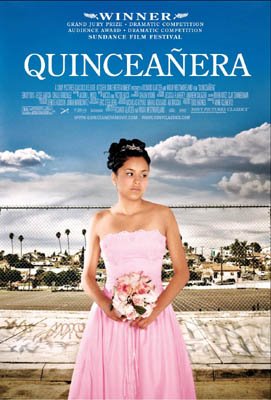

Of course, "Quinceañera's" seemingly humble approach masks deeper ambitions: to get at the heart of untold stories, revealing fresh American tales.

Set in Los Angeles' Echo Park district, the film is keenly observant in a loving but not overly sentimental way about a neighborhood in economic and racial transition.

A quinceañera is a Latino celebration that marks the transit of a 14-year-old girl into womanhood.

At the movie's start, Magdalena's cousin Eileen commemorates her sojourn with a party of solemn pomp and rump-shaking circumstance. The festivities even include the use of a rented white Hummer stretch limo. A quinceañera's demands recall the bankrupting obligations Jewish parents face come their kid's bar or bat mitzvah.

Magdalena, just months from her own quinceañera, is different from her better-off cousin. She doesn't require the event's accessories because she understands its religious, cultural significance. Or, so, thinks her preacher father, Ernesto (Jesus Castaños-Chima).

He's half right about his daughter's serious side.

Newcomer Emily Rios, 15 during the shoot, gives Magdalena the complex maturity bright teen girls often have. Her relationship to nearly-as-serious-but-puppy-dog boyfriend Herman (J.R. Cruz) is full of responsible gestures and teen fumblings.

Still, all her independence doesn't change the fact she wants a Hummer limo. What she gets is a humdinger, when she finds out she's pregnant. But, how? She and Herman never had intercourse. When she insists on this, her father, already ashamed, becomes unforgiving. (Part of the charm of the movie, is how it avoids an easy magical realism about virgin birth.)

Stubborn herself, Magdalena moves into her great uncle's home. The old man (Chalo Gonzalez) lives in the back apartment of a building a white gay couple has purchased and renovated.

Tio Thomas has sold champurrado (a hot beverage) in the neighborhood for years. His home, complete with an outside-art shrine, is a refuge. Great nephew Carlos (Jesse Garcia) already found shelter there, after his parents threw him out, possibly because he's gay.

Tio Thomas embodies the deep core of value of "Quinceañera." When he stands with his back to Carlos and expresses a wish for his happiness, it's powerful. It's not just the words he utters, even his posture invites the heart-cracking release that comes from unconditional acceptance. At one point, Carlos refers to him as a saint. There is something beatific and healing in Gonzalez's performance.

Severing family ties suddenly brings on some of the most torrid and conflicting emotions human's face - especially for a kid. The more family matters, the more exile torments. Yet, "Quinceañera" never becomes operatic. It's no telenovela.

Nor do the tag team filmmakers Glatzer and Westmoreland treat the tectonic rumblings beneath Echo Park as Richter scale disasters.

Transplanted Angelenos and Echo Park residents, the two take to heart (and to task) the benefits and risks of divergent cultures converging. Some of the most chilling scenes in the movie take place around the dinner table of first-wave gentrifiers, landlords and lovers Gary and James (David W. Ross and Jason Wood).

"Quinceañera" is an intelligent, hopeful work. What it doesn't have in flash and outbursts, it trusts to the lived details. Possibility and truth, it asserts gently, convincingly, reside there.

from The Denver Post / Lisa Kennedy

No comments:

Post a Comment